For the Women, Peace and Security agenda to genuinely contribute to ending armed conflicts and fostering more sustainable peace, countries—including Slovakia—must ground their policies in dialogue and partnership with women’s and feminist organizations. However, the Slovak government is instead seeking to restrict the work of the non-governmental sector, and its recent constitutional amendment runs counter to its international commitments.

In 2025, the world marks the 80th anniversary of the founding of the United Nations. Slovakia, then part of Czechoslovakia, was among the 51 founding members committed to preventing conflict, upholding human rights and fostering lasting peace. Yet, despite these noble aims, conflicts have not always been averted. Even today, dozens of armed conflicts continue across the globe, and human rights violations remain widespread.

According to a report by the UN Secretary-General published in August this year, sexual violence — to which women and girls are disproportionately subjected — continues to be used as a weapon of war, intended to humiliate, torture and silence political dissent.

From the outset of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine up to June 2025, UN agencies in Ukraine documented more than 430 cases of conflict-related sexual violence, with women and girls making up the majority of victims. Yet Russia, as a permanent member of the UN Security Council, continues to wield its veto power to block proposals for binding resolutions aimed at ending the war and ensuring compliance with international law.

Rising Conflicts and Undermining Gender Equality

The risk of conflict worldwide is on the rise. According to the Uppsala Conflict Data Program, by the end of 2024 the number of active conflicts had reached its highest level since the end of the Second World War. The nature and actors of these conflicts are also changing. Alongside governments and regular armed forces, non-state actors are increasingly contributing to global insecurity, aided by easier access to funding, weapons and social media platforms.

Technological advances and the spread of artificial intelligence are giving rise to new, hybrid forms of warfare. Defending against these threats requires comprehensive institutional, economic and energy resilience, as well as effective protection against disinformation. Meanwhile, climate change and limited access to essential natural resources are heightening the risk of local conflicts and driving migration. In response, many countries — including those within the European Union — are increasing their defence and arms expenditure.

Alongside growing militarisation, there has been a rise in resistance from far-right and national conservative groups to what they label as “gender ideology.” In many countries, non-governmental organisations promoting women’s rights face legislative and financial restrictions that hinder their work. In parts of the European Union, opposition to so-called “Brussels progressivism” has become increasingly vocal, portraying it as a threat to national sovereignty and cultural identity. These movements often seek to pit women’s rights against so-called traditional family values, deliberately undermining international commitments to gender equality.

This trend has also reached Slovakia. In September this year, the Slovak Constitution was amended to recognise only two genders — male and female — and to assert the country’s sovereignty in cultural and ethical matters, such as the protection of what are described as the “traditional values” of marriage, family, language and culture. Critics warn that the amendment risks undermining Slovakia’s international commitments and the principles it has pledged to uphold as a member of the United Nations and the European Union, including those relating to women’s rights and gender equality.

The Women, Peace and Security Agenda – an Untapped Opportunity?

Looking back, the situation 25 years ago seemed full of promise: a genuine effort to build sustainable global peace, strengthen multilateral cooperation, and coordinate actions to reduce poverty, expand access to education and healthcare, and promote equality. The adoption of the Millennium Development Goals in 2000 reaffirmed the aims of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, which called for stronger international humanitarian law to protect women in armed conflict and for greater participation of women in decision-making — both seen as essential conditions for lasting peace. UN Security Council Resolution 1325, adopted in the same year, marked a major victory for women’s organisations and gender equality advocates, opening doors to areas that had long been dominated by men. Between 2000 and 2019, a further nine resolutions were adopted alongside Resolution 1325, all calling for the meaningful participation of women in decision-making on peace and security, and for stronger protection of women from conflict-related sexual violence.

At the national level, action plans — now numbering over one hundred — have become the main tool for putting the Women, Peace and Security Agenda into practice. Slovakia adopted its first such plan for 2021–2025 in 2020. The plan is coordinated by the Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs and implemented in cooperation with the Ministries of Defence, Interior, and Labour, Social Affairs and Family.

In reality, however, it remains a largely formal document, little known to the public. It serves mainly as a summary of Slovakia’s existing commitments stemming from its membership in the EU and NATO, and as a demonstration of its intent not to fall behind countries that adopted their action plans earlier — Denmark being the first, in 2005.

The plan aims to raise the profile and increase the participation of women in diplomacy, international missions, defence and security, while also providing better protection for migrants, refugees and asylum seekers against abuse and human trafficking. It was drafted without the direct involvement of women’s NGOs — not necessarily because they were excluded from the process, but because, prior to 2020, they had yet to engage with the Women, Peace and Security Agenda.

The plan has no dedicated budget, and its monitoring and coordination processes are largely procedural, offering little scope for genuine evaluation. The ministries responsible for implementation submit reports to the coordinating body — the Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs — which, however, lacks the capacity to properly analyse or verify the information it receives. Independent assessments, for example from civil society organisations, are also absent.

For all its shortcomings, the plan still marks a step forward in Slovakia’s efforts to meet its international obligations on gender equality and women’s rights.

Protecting Women Instead of Involving Them in Conflict Prevention and Resolution

The new plan for 2026–2030 will be drafted in a context vastly different from that of five years ago. The war on Slovakia’s doorstep, together with the worsening global security environment, has changed much — including how women’s experiences of conflict, and their potential roles in its prevention and resolution, are perceived.

After the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, several women’s organisations in Slovakia redirected their work to support female refugees, focusing in particular on preventing and addressing gender-based violence. New initiatives and grassroots groups also emerged, at first providing humanitarian and psychological assistance. Over time, some have broadened their efforts to include integration, violence prevention, leadership development, negotiation and mediation training, as well as supporting the economic inclusion of women at the local level — including those from marginalised communities and refugee backgrounds.

International cooperation has also intensified. UN agencies such as UNHCR and UNICEF have returned to Slovakia to provide technical assistance to the government and the non-governmental sector in responding to the impacts of the refugee crisis. In recent years, several international events have been held abroad to share experiences with the implementation of national action plans, with Slovak representatives taking part. Similar events have also taken place locally, organised by feminist organisations such as ASPEKT, as well as by training institutions affiliated with the ministries responsible for implementing the plan.

The Women, Peace and Security Agenda has gained greater visibility, particularly within the defence and security sectors. For women’s and feminist organisations, this offers a chance to link their core work with efforts aimed at conflict prevention, peacebuilding and greater participation of women in decision-making. Yet this potential remains largely untapped.

As work begins on the second plan, it will be essential to build on the experience and knowledge gained over the past five years. The new plan must also reflect the emerging security risks discussed earlier. At the same time, it should avoid what international feminist organisations involved in the drafting of Resolution 1325 have long warned against — the co-opting of the Women, Peace and Security Agenda by state institutions and military and security forces, and its reduction to a narrow focus on protecting women in conflict situations. The current Slovak plan places strong emphasis on women’s roles within the armed forces and security services, as well as on their protection. However, it gives little attention to initiatives such as peace education, conflict prevention and resolution at the local level, women’s participation in decision-making, or support for their economic empowerment. These areas form the foundation of the broader concept of human security, which underpins the Women, Peace and Security Agenda — and they are typically championed by women’s and feminist organisations.

To move beyond a mere summary of Slovakia’s existing obligations under the UN, NATO and the EU, the new Action Plan must become a shared commitment across society. It should strengthen and expand cooperation between government bodies and civil society, particularly women’s organisations. However, establishing such partnerships remains a considerable challenge, requiring constructive dialogue, mutual trust and respect — qualities that have been weakened in recent years by legislative measures restricting NGOs’ independence and access to funding.

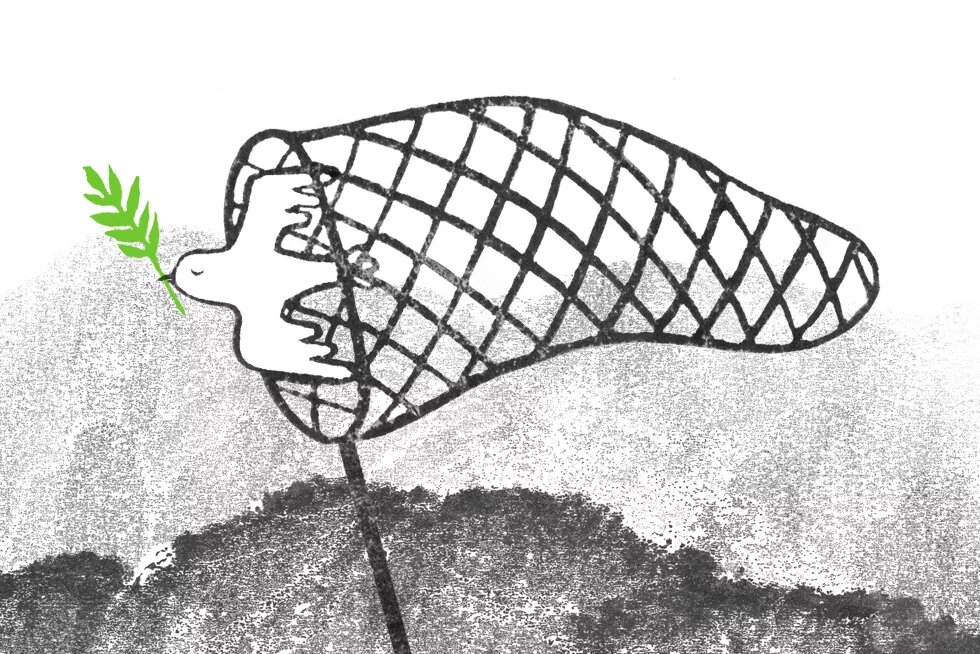

Without genuine cooperation, the new plan risks remaining a purely formal document rather than a practical instrument for implementing the Women, Peace and Security Agenda. After all, the goal that women’s organisations fought for when Resolution 1325 was adopted 25 years ago was not to make war safer for women — but to end war itself.

The views and opinions in this text do not necessarily reflect those of the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung.